The inexplicable charm of Pietro Marcello’s new film Scarlet (L’Envol) presents itself in a curlicued elegance; convoluted and drifting, but nonetheless spellbinding. Marcello, who seemed to refresh the air of the current European cinema with the exquisite Martin Eden and offered a new prospect of the Italian filmmaking scene with an allusion to and perhaps beyond Bernardo Bertolucci or Roberto Rossellini, composes yet another opus laden in his unique mode of classicism. Such feeling of witnessing a new wave of classics emerge is always a delight, and it seems that more often than not, Marcello’s films seem to trace history and simultaneously transcend the present.

But what exactly is this Scarlet? Marcello’s films always appear as an anomaly at first glance. Martin Eden was an Italian adaptation of a novel set in Oakland, California, amalgamating Marcello’s natural documentary instinct with a sense of narrative mise-en-scène to produce a peculiarly elegiac artistic vocation. His first French film Scarlet is also a convolution of many laces; a helix with the threads of history, neorealism, musical, fable (somehow evoking both Jacques Demy and Pasolini at the same time) and at its center, a contemplation on the magical integrity of romanticism and art as a combatant against history’s gravitas over our lives.

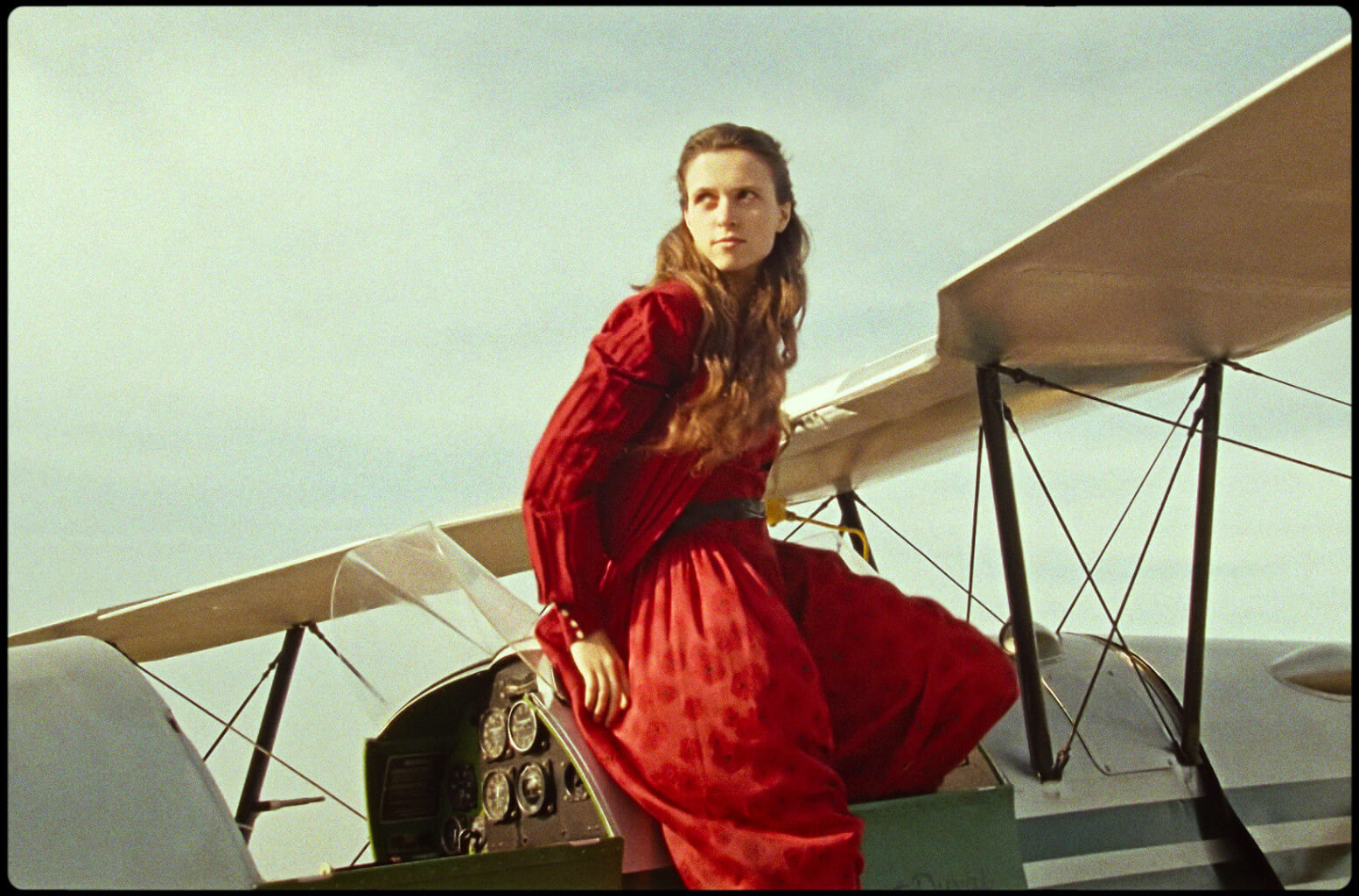

The film’s spontaneous journey initially follows Raphaël (Raphaël Thiéry), a World War I veteran who returns only to find his wife dead and his baby daughter motherless. Raphaël’s proletarian ordeals are inertly bordered by a looming presence of some mystic force, until it slowly begins manifesting in young Juliette who must bear the torch of his dilemmas as the story takes on new shapes with passing time – a witch makes an appearance to spill some ominous prophecy that will haunt the rest of the film, and a man drops right off the sky at the moment of romantic fervor. Juliette, decidedly played by ethereal Juliette Jouah, becomes the prime agent of the film’s optimism and reverie. She can burst straight into a musical number and still perpetuate the grittiness of practical, pastoral France where incessant labors and small town politics can daunt anyone’s identity. Lit under the orange sunlight and bathed by the blue night air (a Vittorio Storaro-level glossy photography shines here), she persists because she knows how to hold onto arts of her own and produce hopes for her own world. Marcello’s new film might not be for those who expected Martin Eden’s perfect study of character and history, but it nevertheless introduces a new tenor of a formidable auteur in the making.